On 20 July, ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) attacked a press conference organized by the Socialist Youth Association Federation and killed thirty-three socialist activists in Suruç. On 22 July, a clash broke out between ISIS militants and Turkish soldiers near Kilis. The following day, Turkish authorities confirmed Turkey’s participation in the US-led international coalition against ISIS and bombed ISIS targets in Syria. That same day, Turkish authorities also initiated multi-faceted operations against Kurdish and leftist circles, including police operations in which more than a thousand activists were detained, as well as air bombardments targeting PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) camps in Turkey and Iraq. Following a two-year-long cease-fire, these operations brought about a new cycle of violence between Turkish forces and the PKK; at least sixty-three members of the state security forces, forty-seven guerillas, and forty-three civilians were killed during the clashes.

Ahmet Davutoğlu, head of the Turkish interim government, described the recent operations as a struggle against three different “terrorist organizations”: the PKK, the DHKP-C (Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party-Front), and ISIS. According to Davutoğlu, Turkey has been under a “three pronged attack,” implying that those actors are directed by a single force that “seemed to press the button” to start simultaneous attacks on Turkey. Considering the political background, social base, and current positioning of each organization—especially the ongoing clashes between Kurdish forces and ISIS in Syria and Iraq—the three-pronged attack conspiracy was hardly convincing. Also, as observed by other commentators, the course of the operations have indicated that Turkey’s three-front war does not include an effective struggle against ISIS. Turkish authorities, instead, took ISIS attacks as an opportunity to launch a new round of assault on Kurds, leftist circles, and the new alliances that have been forged among them, despite the fact that these pro-Kurdish and leftists circles have been attacked by ISIS and other jihadist groups (as happened in the Suruç attack).

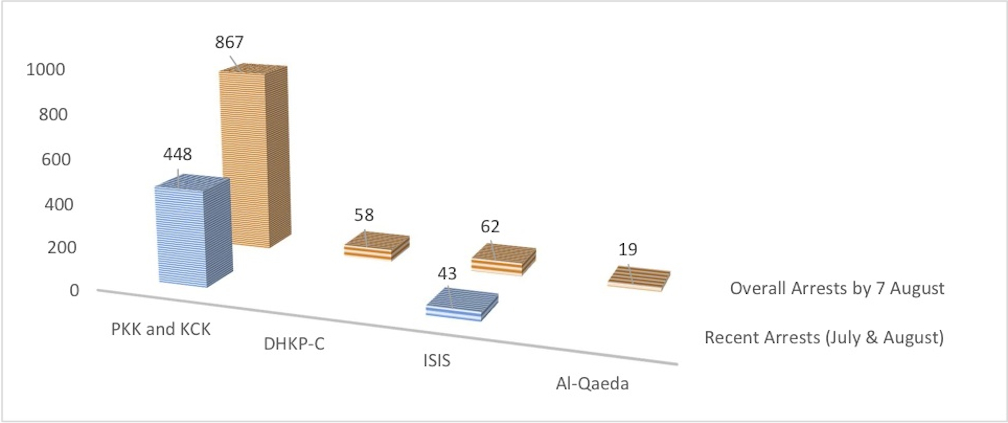

For example, the number of arrests made in the anti-PKK operations over the last month is at least three times more than the arrests made during the anti-ISIS investigations over the last six months (see Table One). Additionally, while the Turkish air force carried out at least fourteen different waves of airstrikes against the PKK and hit more than four hundred targets, it conducted just one anti-ISIS air operation, hitting three targets in the last month (on 29 and 30 August, Turkish air forces finally joined the coalition forces’ airstrikes and hit thirteen other ISIS targets). Besides the reluctance towards tightening its borders against jihadist groups, the Turkish government has continued its hostility towards the Syrian Kurdish PYD (Democratic Union Party) and its armed wings, the YPG (People’s Protection Units) and YPJ (Women’s Protection Units). In fact, Turkish authorities have been blocking and delaying even the funerals of YPG-YPJ fighters who are Turkish citizens, not allowing their remains to enter Turkey. Turkish authorities were also recently accused of handing over six wounded YPG fighters to the jihadist Al-Nusra Front.

Considering the course and scope of the operations, it seems that Turkey’s real three-front war has specifically targeted three separate pro-Kurdish fronts: (1) the PKK, (2) the HDP (People’s Democratic Party), and (3) the PYD.

[Table One: It is difficult to track the exact number of arrests made during the recent operations. But there is still a significant difference between the number of arrests for PKK-related allegations and ISIS-related allegations considering reports of arrests provided by different sources. On 7 August, Anatolian Agency reported the overall number of arrests under the terror allegations with their distribution among the organizations. Major national newspapers (Milliyet and Hürriyet) have reported at least 448 arrests made for PKK-related allegations and forty-three arrests for ISIS-related allegations during the recent (July and August) anti-terror operations. On 24 August, the minister of interior affairs stated that 121 people are currently under arrest due to ISIS-related allegations. On 28 August, the HDP also reported that 298 people were arrested between 7 June and 26 August.]

The First Front: The PKK

Following the Suruç attack, two police officers were found killed in their apartments. A local pro-PKK group claimed responsibility for the attack, even though the KCK (Group of Communities in Kurdistan), an umbrella organization of which the PKK is a member, stated that they had not known about the attack. The Turkish government cited the execution of police officers as an excuse to initiate the new cycle of clashes with the PKK, ending the peace process that began when the PKK declared a cease-fire in March 2013.

Although the execution of the police officers seemed to provide the apparent rationale behind the attacks on the PKK, Turkish authorities have been criticized for abusing the peace process and preparing for a new cycle of war with the PKK for months. In fact, throughout the peace process, a sense of insecurity and distrust has emerged among the Kurdish population towards Turkish authorities. In addition to increasing state presence through police patrols and checkpoints alongside withdrawal of the guerilla forces, the Kurdish people were subjected to various attacks by state forces, as well as by jihadist groups that state authorities were blamed for either protecting or overlooking. For example, during the ISIS attacks against the Syrian Kurdish town of Kobanê in September and October 2014, Turkish authorities denied help to Kurdish forces and left the people of Kobanê in danger of genocide. During the ensuing Kobanê protests on 6 and 7 October, more than fifty civilians were killed by either state forces or armed jihadist militias in Turkey’s Kurdistan. Yet there has not been any effective investigation conducted by Turkish authorities regarding these killings.

More recently, during this summer’s elections, there have been more than one hundred attacks against the pro-Kurdish HDP, and there has been no effective investigation into these attacks either. Two days before the elections, an HDP activist was killed in Bingöl; the perpetrator(s) has not been found yet. A day before the election, a bomb was exploded at an HDP election rally in Diyarbakir; four people were killed and around two hundred were injured. It was later revealed that the bomb was detonated by an ISIS member who had been briefly detained and then released by the Turkish police two days before the attack. Amid the rising sense of insecurity among Kurdish people, on 11 July, more than a week before the Suruç attack, the KCK declared that the peace process had been suspended by the Turkish authorities and blamed the Turkish state for conducting war preparations, referring to the ongoing arrests of Kurdish activists and the construction of military stations, roads, and dams. Following the declaration, PKK forces started erecting roadblocks and ID checks, as well as attacking dam construction sites and setting construction vehicles on fire.

The Turkish government’s attacks on the PKK will not undermine but rather deepen the sense of insecurity and distrust among the Kurdish people. With the deepening sense of insecurity, the PKK further establishes itself as an alternative source of protection and authority on the ground. Alongside the recent cycle of violence, there have been reports of torture and extra-judicial killings committed by state authorities. These developments have been particularly reminiscent of the state violence of the 1990s, further deepening the sense of insecurity among the Kurdish people. As of 20 August, in sixteen districts and cities of Turkey’s Kurdistan, People’s Assemblies (Halk Meclisleri) declared self-governments, denying the legitimacy of state authorities and institutions.[1] It still seems unclear to what extent such declarations would effectively undermine Turkish state control. In fact, Turkish authorities have reacted harshly to the self-government declarations, arresting Kurdish politicians, imposing curfews, and targeting civilians in Silopi, Cizre, Varto, Şemdinli, Silvan, Lice, and Yüksekova. Yet the self-government declarations and the Turkish authorities’ reaction to them have once again confirmed the deepening sense of insecurity and distrust towards the Turkish authorities in Kurdistan.

The Second Front: The HDP

The general elections of 7 June marked a turning point for Turkey. For the first time, the pro-Kurdish and leftist HDP received thirteen percent of the vote, surpassing the national election threshold and thus entering parliament. Although the election system had discriminated against pro-Kurdish parties in the previous elections, this time the election system favored the HDP and brought the party eighty seats, as many seats as the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) won with its sixteen percent of the vote. In addition to electoral support from various leftist groups, the HDP garnered most of the Kurdish votes and won fifty-three seats from the Kurdish-populated eastern provinces. Although the Justice and Development Party (AKP) had earned forty-three seats from these provinces in the previous (2011) elections, this time they only captured seventeen seats. In other words, the HDP’s electoral victory cost at least twenty-six seats to the AKP in fourteen eastern provinces.[2] With these twenty-six seats in addition to its current 258 seats, the AKP could have obtained a parliamentary majority (276 seats) and formed a one-party government. Meanwhile, in eight coastal and western provinces, the HDP won an additional eleven seats away from the AKP.[3] In addition to those losses to the HDP, the AKP also lost at least twenty-two seats to the MHP in twenty central, mid-western, and northern Anatolian provinces.[4] As a result, the AKP lost its twelve-year-long governing majority, and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s plans for introducing a presidential system were accordingly canceled, or at least postponed.

Following the anti-terror operations and the clashes with the PKK, AKP circles started defaming HDP members, blaming the HDP for abetting “terrorism.” While authorities started anti-terror investigations and operations against HDP members, including co-chairs Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ, it was also claimed that there have been preparations to ban the HDP, or at least deprive the party of treasury aid through a court ruling. As mentioned above, the discursive and physical attacks against the HDP did not begin after the elections. During the election campaign, in more than a hundred incidents, HDP members and/or events were attacked. Yet the recent anti-HDP campaign seems aimed at undermining the HDP’s electoral support and preventing another electoral victory that the HDP may win in an early election.

After the talks for forging a coalition government between the AKP and the Republican People’s Party (CHP) failed, the MHP also refused to either forge a coalition government with the AKP or to support an AKP-led minority government. Since the failure to form a new government requires an early election (erken seçim)—which President Erdoğan has preferred to call a “repeat election” (tekrar seçim), as if the June election was not valid and needed to be repeated—an early election is now expected to be held on 1 November. Through attacking and delegitimizing the HDP, AKP circles may not only hope to cause the HDP to lose electoral support, but also to gain nationalist votes from the MHP in an early election. However, even though AKP circles may succeed in gaining some of these nationalist votes, their strategy of marginalizing pro-Kurdish politicians and institutions would concentrate the Kurdish votes and further distance the AKP from Kurdish electors. Without winning Kurdish votes back, the AKP could neither form a strong one-party government nor mobilize parliamentary support for establishing a presidential regime. In the current election system, nationalist votes would, at most, enable the AKP to obtain a parliamentary majority with a small margin and form a weak one-party government. In fact, as the recent election polls showed, the HDP seems to be maintaining, and even increasing, its electoral support. A strong AKP government seems possible only if one of the four parties fails to surpass the national threshold in the early election. Although the HDP has been seen as the most likely party to fail surpassing the threshold, recent analyses also address the possibility that AKP circles might be aiming to make the MHP lose votes and thus fail in surpassing the threshold.

Additionally, there has also been speculation about the plans for setting up polling stations only in urban centers throughout Kurdistan, and in doing so, undermining the electoral support that the HDP would get in an early election. In fact, in the previous weeks, both Prime Minister Davutoğlu and President Erdoğan mentioned this option of not setting up polling stations in certain rural areas for the sake of “election security” in the wake of the ongoing clashes. However, in the elections of 7 June, in various eastern provinces, there was no significant difference between the votes that the HDP received in urban areas and the votes it received in rural areas.

The Third Front: The PYD

The general elections of 7 June were also followed by the unexpected advances of the Syrian Kurds against ISIS. Following a two-week-long operation, on 15 June, the YPG-YPJ, together with forces from the Free Syrian Army associate Burkan Al-Firat, took control of Tel Abyad, located alongside the Akçakale-Tel Abyad border-gate, from ISIS. With the capture of Tel Abyad, two Kurdish cantons, Jezeera and Kobanê, were thus geographically connected with each other and Kurdish forces started controlling most of the Turkish-Syrian border. With the loss of Tel Abyad, ISIS lost its main logistical access to Turkish territory. This development alarmed Erdoğan, who read Kurdish advances as an indication of a Western conspiracy to open a Kurdish corridor in Syria through “bombing Turcomans and Arabs while placing the terrorist PYD and PKK in lieu of them.”[5] The Syrian Kurdish advances not only agitated Turkey’s anti-Kurdish policy in the region, but also significantly undermined the jihadist groups that Turkey has been supporting under its policy of toppling Bashar Al-Assad’s regime.

Turkish authorities used the recent PKK attacks to argue that the PYD poses a serious security threat to Turkey, stressing the links between the PKK and the PYD, despite the fact that the PYD has not shown any hostility towards Turkey. With its airstrikes against the PKK, Turkey confirmed its participation in the international coalition against ISIS. According to US sources, the negotiations about Turkey’s participation in the international coalition took nine months and were concluded on 8 July, about three weeks after the YPG’s capture of Tel Abyad and twelve days before the Suruç attack. By joining the coalition, Turkey has aimed to have an influential role in Syria and eventually to undermine the Syrian Kurdish advances. For example, during the negotiations, Turkish authorities have insisted on the creation of a safe zone between Jarablus and Mare along the border and seemed eager to sponsor such a zone with Turkish military force. This zone would primarily block a possible territorial link between Afrin, the third Kurdish canton, and the Kobanê and Jezeera cantons. It would also ensure Turkish access to non-Kurdish Syrian opposition groups, including jihadist groups, which Turkey may continue to mobilize against the Syrian Kurds.

However, Turkey’s anti-Kurdish strategy in Syria would be limited due to the fact that Syrian Kurdish forces have emerged as the most reliable force for the creation of a democratic Syria on the ground. In fact, the YPG and YPJ forces have been particularly reliable not only because of their secular and egalitarian political projections, but also due to the fact that they relied on a significant level of local support, unlike the jihadist groups, which mainly relied on foreign fighters. As the course of the civil war has shown, without mobilizing a certain level of local support, an opposition group could hardly stand against the Syrian regime and/or jihadist groups even with the support of the international coalition. A dramatic example is the unfortunate fate of the first US-trained rebel group. It was reported that after completing the US-led train-and-equip program in Turkey and proceeding into Syria, five fighters were killed, sixteen were wounded, and thirty-one were kidnapped by the Al-Nusra Front. Only two fighters remained from the group of fifty-four US-trained fighters.

Turkey’s three-front war seems unsustainable not only ethically, but also from the perspective of real-politics. Turkey’s attacks on Kurds would increase the feeling of insecurity and, hence, the demand for self-protection and self-government in Turkey’s Kurdistan. Ostracizing the HDP would not undermine, but further consolidate, the political mobilization of the marginalized and oppressed groups that the HDP has brought together. Turkey’s hostility towards the PYD and other Syrian Kurdish groups would continue to block Turkish authorities from respecting a democratic transformation of Syria, which Syrian Kurds would also be part of. Most importantly, this three-front war might bring about a civil war at larger geographical, political, economic, and material scales. The latest ongoing war has already damaged ‘the period of no clashes’ (çatışmasızlık dönemi) in Turkey’s Kurdistan and has cost more than a hundred and fifty lives.

NOTES

[1] Şırnak city center, Silopi, Cizre, Nusaybin, Yüksekova, Varto, Bulanık, Hakkari city center, Van-İpekyolu, Van-Edremit, Diyarbakır-Sur, Silvan, Lice, Batman-Bağlar, Doğubeyazıt, and Hizan. In Istanbul, in self-governments were also declared in two neighborhoods, Gulsuyu and Gazi.

[2] Şanlıurfa, Mardin, Diyarbakır, Batman, Siirt, Şırnak, Hakkari, Van, Bitlis, Muş, Ağrı, Kars, Erzurum and Gaziantep.

[3] İstanbul, İzmir, Ankara, Bursa, Mersin, Antalya, Adana and Kocaeli.

[4] Bursa, Aksaray, Ankara, Zonguldak, Samsun, Giresun, Gümüşhane, Bayburt, Sivas, Nevşehir, Kayseri, Kırıkkale, Kırşehir, Uşak, Çanakkale and Karabük.

[5] A link in Turkish can be found here.

![[Recently constructed Turkish military post near the Iranian border, an area recently declared a temporary security zone due to guerilla activity. Image by Firat Bozcali.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Firat_three_photo.jpg)